For a summary version of this paper, please click here.

Introduction

The word ‘Islamism’ has come to occupy a central place within the canon of western scholarship when describing Muslims who seek any form of political autonomy or governance that is tied to their faith. In popular narratives in the media, the word is often associated with others giving the impression that it relates to an ever-constant threat posed by Muslims, hence the ubiquity of terms like ‘Islamist extremists’ or ‘violent Islamists’. Within many academic circles, there is an assumption that the word ‘Islamist’ is a value neutral analytical category used as a descriptor for Muslims who express political ambitions.

This paper will seek to problematise the word ‘Islamist’, predominantly by highlighting the colonial origins of the word, and the way it was traditionally used as a euphemism for Muslims who were seditious to colonial/imperial interests. Chiefly concerned with a ‘Pan-Islamism’ movement that sought to politically unify the Muslim world – by recognising the Ottoman Sultanate as being the spiritual and political leader of all Muslims – British officials made a concerted effort to subvert this movement from gaining any hold over their Muslim populations. Colonial era archives reveal that while the British were effective in producing obsequious colonial elites within their territories, they did not fare as well in making a compelling case to the average Muslim living within the Empire – that the concerns of the ummah and their political unity with their co-religionists was not centrally important to the common Muslim. Spiritual connectedness of the ummah has stood in sharp contrast with the political realities of Muslim governance and political ambition. As Azmi Özcan writes in his seminal work on pan-Islamism,

Theoretically, Islam recognizes no division of geographical boundaries or nationalities among its followers. Therefore, Pan-Islamism in the sense of a union of all Muslims, is in fact as old as Islam itself, finding its roots in the verses of the Qur’an and the traditions of the Prophet. This might be the case in theory, but in reality the circumstances associated with the rapid expansion of Islam did not even allow a realization of cultural unity, let alone one of political unity.1

Özcan’s work highlights well how colonial fears of ‘pan-Islamism’ presented these political connections as something new, but that from the sixteenth century, regional powers had sought the protection and support of the Ottoman Sultan based on the notion of Ittihad-i Islam – bringing Muslim rulers in India, Central Asia and Southeast Asia into their concern.2

This paper does not seek to tread over old ground, nor does it seek to make a case for Muslim political unity as so effectively done by Ovamir Anjum in his piece ‘Who Wants the Caliphate?’. That work is being discussed and debated, and will, at the very least, allow for new imaginings of what a world for Muslims might look like. What I will take from Anjum’s piece though, is the framing for this paper by situating the ummah and caliphate on a longer and broader timeline than 1870s western anxieties over pan-Islamism,

At a minimum, caliphate means Muslim unity expressed in political terms, and as such, it is hardly an idea Muslims need to reinvent. It is present in every Qur’anic lesson on social existence, every Prophetic teaching, and every Friday sermon to this day. Throughout history, Muslims have agreed on the need for a political actualization of this idea; it not only predated Islamic law but was a condition of its birth and coherence. In reality, the caliphate did not always include all Muslim regions, and the idea of a total pan-Islamic unity has been an aspiration only rarely attained.3

With that said, this paper’s focus will be on the ways in which ‘pan-Islamism’ (and ‘Islamism’ in a contemporary context) was securitised to the extent that it signifies little more than the notion of a Muslim threat to European political and colonial ambitions. Over the course of this essay, I will seek to highlight how colonial administrations engaged with Muslim political concerns, but also how they engaged with the faith itself. What I hope will become evident by the end of this paper, is the idea that use of the word ‘Islamism’ produces a false political dichotomy, which allows the use of religious discourse in order to maintain the status quo of despotic nation states but casts the use of religious discourse to conceive of alternative realities as not only politically seditious, but religiously heretical.

In his ‘Recalling the Caliphate’ Salman Sayyid informs us that ‘Islamism’ is the desire to, “establish a political order centred on the name of Islam.” Sayyid differs from colonial Orientalists in his view that ‘Islamism’ is a, “constellation of political projects that seek to position Islam in the centre of any social order,” rather than being a specific ideology or distortion of Islam.4

Immediately following these contentions around the word ‘Islamism’, Sayyid suggests that the work of decolonisation is the project of ‘Islamism’ itself, as it seeks to unravel the colonial dominance of the West.5

Wael Hallaq takes a different approach. Unlike Sayyid, he believes that ‘Islamism’ replicates the structures of modernity in a way that does not permit it to ever truly be subversive to the central domains of Euro-America, for example in an ‘Islamic finance’ system that is not in any, “structural way different from the central domain of modern capitalism.”6 For Hallaq, ‘Islamism’ is in a dialectical relationship with western modernity, and so such modern projects are inhibited in their ability to be truly decolonial.7

The work of Sayyid and Hallaq is important, but I wonder to what extent it is possible to decentre from a West where the frame of ‘Islamism’ remains predominantly a pejorative term for those who concern themselves in the affairs of the ummah. Further still, it is my contention that while less measurable in terms of a material project, the very notion of spiritual concern for the well-being of other Muslims around the world is the basis for any understanding of the well-being of the ummah, rather than in the existence of a political outcome, or the efficacy of any particular action. It is in this concern – tied to an understanding of worshipping Allah8– that will continually provide the foundational block of subversion to ideologies or systems of governance that seek to foster and maintain divisions between Muslims.

My desire to push Sayyid’s work further, and to reject the use of the word ‘Islamism’ is precisely located in one of his own central critiques of Western uses of the term,

The various attacks on Islamism on the grounds of its purported essentialism are only possible by evoking an essentialist notion of the Western enterprise, which is able to uncover the Western essence even in the most determinedly anti-Western discourse. The conceit in which the West is universal and the non-West is particular animates many of the Enlightenment fundamentalists. The universal can no longer be a euphemism for the Western project, nor can the particular be simply considered nothing more than the periphery of the West. The continuing presence of various Islamist groups (and various other movements) indicates that the West can no longer be the uncontested template by which we give shape to the world. One of the reasons that Islamism is seen as a disruptive force is that it fails to accept this juridical role of the West. Many of the critics of Islamism are often merely content to try and reinscribe a de facto Western hegemony in the guise of universalism, instead of recognising that there is a need to develop different language games that do not presuppose the juridical function of the West, especially juridical functions that come armed with a panoply of colonial violation and violence.9

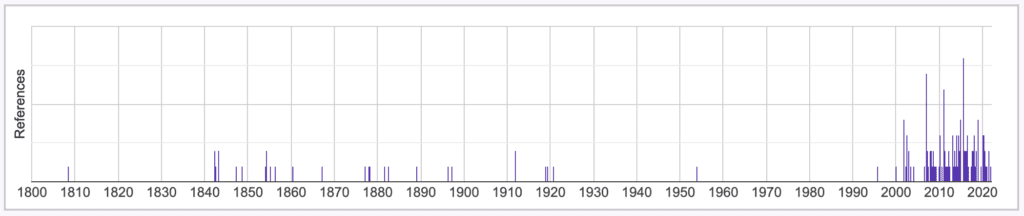

It is precisely in the last sentence of these words from Sayyid that this piece proposes a scrapping of the use of ‘Islamism’ – particularly due to its place within the edifice of colonial violation and violence. A search through Hansard of British Parliamentary debates around words such as ‘Islamism’ and ‘pan-Islamism’ reveal British concerns about Muslims engaged in discussions of the ummah were seen as seditious. A graphical view of these debates presents spikes in two particular periods, an increased discussion around the Great Rebellion of 1857 in India, and then again in the contemporary period after al-Qaeda’s attack on the US on 11 September 2001.

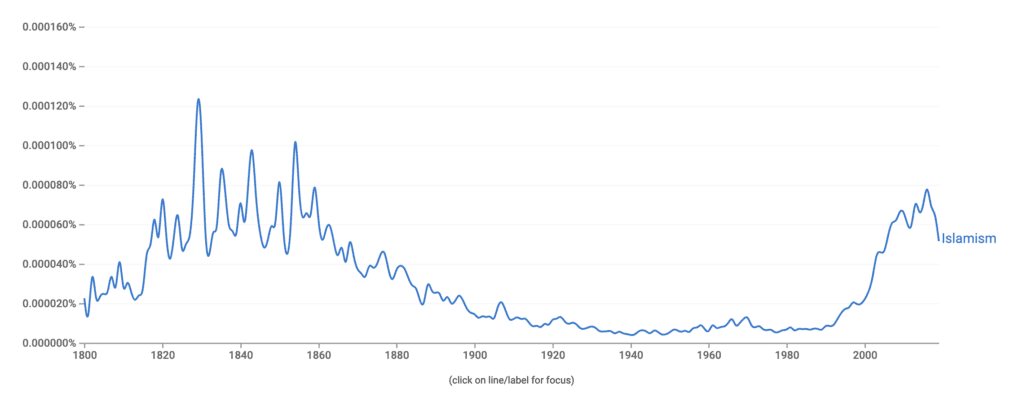

The trend of British concerns around ‘Islamism’ and ‘pan-Islamism’ being tied to Muslim organising around the ummah presenting an ‘existential threat’ is reinforced in an Ngram analysis of the Google Book archive that permits an analysis of their digitised content from 1800 to 2019. Replicating the debates within Parliament, we see heightened concerns in the period of the mid-1800s, and then again in the contemporary period.

While not all uses of the word ‘Islamism’ in the earlier periods were pejorative, when invoked as part of the formula ‘pan-Islamism’, it took on the meaning of a threat. This began before the Ottoman project to politically unify the ummah, but it was from the 1870s onwards that ‘Islamism’ really took on its pejorative meaning. The 1876 government-commissioned Hunter Review on the loyalties of Indian Muslims to the Queen is emblematic of how the notion of an ummahwiy connection between Muslims came to be pathologised as seditious to British political interests, with ‘Islamism’ and ‘pan-Islamism’ being presented as a perversion of ‘true Islam’. These same colonial narratives have come to be almost verbatim repeated in the post 9/11 context, as Muslim belief is problematised by policymakers. One example of this comes in a discussion on Muslim faith schools in 2006 from British parliamentarian, Paul Goodman,

As I see it, there are three features of Islamism. One is the extreme distinction that it draws between what it calls the “house of Islam” and the “house of war”. I understand that it is not a feature of mainstream Muslim thought. Secondly, the Islamists argue that the loyalty of Muslims is primarily, politically, to the umma—the body of Muslims worldwide—and not to the country in which they happen to be living. Thirdly, there is the question of the application of the sharia.10

Almost in an act of necromancy, Goodman’s remarks are eerily reminiscent of WW Hunter’s, albeit 130 years apart.

What are the common features of the concerns being expressed around ‘Islamism’? To understand the etymology of this word, it is important to study the way it was used in the colonial period, and how it came to occupy such a central role in the way that the dissident and subversive Muslim was constructed. Some might point to the Arabic word islamiyyun as an equivalent to ‘Islamists’ in its common use, but I would argue that the two terms bear little in relation to one another, primarily due to the history and intention that is foundational to the popular use of the latter.

The conservative journalist Peter Oborne summarises my key concern on the use of ‘Islamism’ well in The Fate of Abraham: Why the West is Wrong about Islam,

terms can be used in various combinations as in ‘Islamist extremist’, ‘extreme Islamist’, ‘Islamist terrorist’, etc. Sometimes they are treated as if they were synonyms (i.e. Islamist and extremist). On other occasions, the terms are used as opposites. Thus moderation is opposed to extremism, radical to moderate. I will show how they have been designed to separate ‘good’ Muslims from ‘bad’ Muslims. The effect is to encourage prejudice against all Muslims, along with the belief that Islam itself is an enemy of British and Western society.11[emphasis added]

In what follows, I utilise a series of case studies to think through the implications of the term ‘Islamism’ by tracing its use throughout the colonial period as ‘pan-Islamism’, up to its continued usage as ‘Islamism’ in contemporary times. To do that, it is important to start before the Great Uprising of 1857 in India, and the British response to it.

The Colonial Roots of ‘Islamism’

1853 – The assassination of Colonel Frederick Makeson

While working on his veranda, Colonel Frederick Makeson, the Commissioner of Peshawar was assassinated on 10 September 1853. Makeson was the most senior British official for the Northwest Frontier Province of India, and thus became a target for political grievance by locals. A Muslim man approached Makeson with a petition, claiming that it needed to be read and as Makeson went to read it, he was stabbed in his chest. It would be another four days before the Commissioner would die of the stab wound.12

During his interrogation and trial, the assassin admitted that he lived in the area of Swat, which at the time was outside of British control. His motives were based purely on the notion that he did not want the British to invade his land. The official report into his act concluded that he was a ‘religious fanatic’ attempting to gain martyrdom.13 After his trial concluded, the assassin was hung as a common criminal with the exception that afterwards he was cremated and had his ashes thrown into a river. The British argued that they did not want his grave to become a shrine or for it to accrue the perception that he died a martyr.14

While the trial concluded the assassin’s status as a ‘religious fanatic’, according to Helen James, there was a deeper underlying history that set this act into motion,

This event followed intimations to the authorities between 1848 and 1852 of a religious organisation consisting of Wahhabis in Patna that was amassing arms, ammunition and men in preparation for a war against the Government of India. Letters and other documents had been seized showing a secret supply route running from Patna to Peshawar via Meerut, Amballa and Rawalpindi, which would enable the conspirators to mount an uprising. Documents from the investigation show that the assassination had been carried out in response to a fatwa, or religious edict, against Colonel Makeson, who had led punitive raids into the NWFP the previous year.15

Popular narratives on the fear of ‘Wahabbis’, ‘Islamists’ and other ‘seditious’ Muslims are often framed in relation to the Great Uprising of 1857, and in particular the work of WW Hunter in framing Muslims as particularly problematic to imperial designs. The killing of Makeson reminds us that Muslims across India were not only concerned with how they were directly impacted by the military actions of the British, but how they saw those actions in relation to the existential threat they felt not only to their lives, but also to their faith. Four years later, these tensions would be magnified to an unprecedented degree.

1857 – The British Response to the Great Uprising

The first half of the 1800s saw British influence in India dramatically increase as a more permanent British army (that included many Indian sepoys) fought campaigns in Afghanistan (1838-42 and later 1878-80), took control of Sindh (1843), and finally the Punjab (1845-6 and 1848-9).16 Following that period, a number of assumptions were made about the Muslim ‘problem’, many of these assumptions being based on the aftermath of the First Indian War of Independence in 1857 – often referred to as the Indian Uprising or the Sepoy/Indian Mutiny.

In many ways, whether based in reality or not, the uprising was very much rooted in the anxieties that both Muslims and Hindus had about the way Christianity was being imposed on them. Policies such as the enabling of Hindu widows to remarry as well as rumours around pig and cow fat contaminating the salt, ghee, sugar and gun cartridges of the sepoys began to feed that wider narrative. According to the Raj historian Lawrence James, the impatience of British officers towards the concerns of the sepoys was a key factor behind their inevitable insurrection.17

Coupled with the above narrative Anatol Lieven claims that there was an added dimension which presented itself as having a distinctly Muslim nature to it, at least according to the British,

The revolt itself stemmed in part from the British abolition the previous year of Awadh, the last major semi-independent Muslim state in north India. In Lucknow, mutinous soldiers proclaimed the restoration of the Awadh monarchy, and, in Delhi, they made the last Mughal emperor their figurehead. Across much of north India, radical Muslim clerics preached jihad against the British.

In consequence, although a great many Hindus took part in the revolt, the British identified Muslims as the principal force behind it, and British repression fell especially heavily on Muslims and Muslim institutions. The two greatest Muslim cities of north India, Delhi and Lucknow, were ferociously sacked and largely destroyed by the British army and its Punjabi auxiliaries, with many of their leading citizens killed. The last vestiges of the Mughal empire were wound up, and many Muslims dismissed from the British service.18

The British had managed to successfully quell the rebellion, but only just. Due to the scale of the rebellion and the extent to which the sepoys had managed to push the British military units, the response by the authorities was inhumane.19 The particularly brutal response of the British was not simply justified in terms of the uprising itself, but was given an extra impetus due to the rhetoric that accompanied it. False or exaggerated stories were circulated that the Sepoy and Indian insurgents were carrying out mass rapes against English women and girls, with one particular story claiming that 48 English girls had been raped in Delhi.20

British newspapers were able to report back from India on an almost daily basis due to telegraph services that had been established. The News of World promised its readers the ‘fullest and exclusive details of Indian atrocities’ developing an anti-Indian sentiment within the British Isles. During a speech at the Cambridge Union, the speaker said of the response,

When the rebellion has been crushed from the Himalayas to Comorin; when every gibbet is red with blood; when every bayonet creaks beneath its ghastly burden; when the ground in front of every cannon is strewn with rags, and flesh, and shattered bone – then talk of mercy.21

The response of the British was to treat the Uprising in the same way they had the Irish in their occupation. This approach led to the enactment of the British Indian Police Act of 1861, which according to Lieven produced a paramilitary approach in India, “charged with holding down a restive population.”22

In 1857, British concern over ‘pan-Islamism’ was somewhat Machiavellian in its nature. The British understood the problem a unified Muslim consciousness might prove to them, but were also not beneath seeking theological assistance from Sultan ‘Abd al-Majid by requesting a proclamation that Indian Muslim subjects of the Caliphate not join the Uprising as the British were at that point the allies of the Ottomans.23

According to Joseph Massad,

This was not the first time the British had asked the Ottomans to invoke their caliphal authority. In the context of Napoleon’s threat to British rule in India half a century earlier, British diplomats, who took the threat seriously, had interceded with the Ottoman caliph to address Indian Muslims and warn them of the “false promises of the French.” Henry Laurens affirms that in doing so “the sultan would thereby engage unawares in pan-Islamism.”24

Ultimately, the British recognised the power of an idea and a historical reality, of an ummah connected spiritually as well as politically through a common authority. Where it suited them, they were willing to use it in order to repress Muslims for their own needs, but at the same time, they came to understand its potential to subvert their authority. In the post-1857 world, the British view was that Muslim political agitation required specific targeting for repression.

1864 – Muhammad Jafar Thanaseri and the ‘Wahabbi’ Trials

One of the key accounts of repression of Muslim scholarly figures after the 1857 Uprising comes from Muhammad Jafar Thanesari who wrote Kala Pani: Tavarikh-e Ajib (Black Water: A strange history). Thanesari was actively supporting the mujahideen in the Yaghistan border area who had established encampments in order to repel British encroachment into the northern areas of India. He had also been implicated in preaching jihad in the mosques of Patna and Delhi encouraging Muslims to fight during the 1857 uprising.25 Thanesari initially managed to avoid arrest, however on the severe torture of his family and friends, he was eventually tracked to Aligarh where he was detained.26

The British authorities took Thanesari to Ambala, where they had convened a special trial system to try those involved with the Uprising and other forms of jihad against the British authorities. Immediately on his arrival, he was tortured into informing on others who might be co-conspirators. He refused to comply, even at the threat of hanging.27 In April 1863, Thanesari was brought before the Court of Ambala as his own brother (Muhammad Sa’id) had been turned as an “approver” (informant) against him after having been subjected to torture.28

At the turn of Thanesari’s brother to give evidence, he retracted his previous agreement and refused to bear false witness against his own brother, leading to a postponement of the trial. During a lengthy trial where Thanesari was not permitted to call witnesses due to the ‘special’ status afforded to the court, his counsel attempted to provide whatever defence he could, in particular focusing on Thanesari’s activities being outside of any British controlled territories.29 After a long period of deliberation with British officials, the judge released his judgement on 2 May 1864, condemning the men to death.30

Despite having accepted his fate as being condemned to death, the British became worried that such executions would come to be seen as martyrdoms for the anti-colonial struggle, and chose instead to send Thanesari and his co-defendants to the Kala Pani prison on the Andaman Islands. The detention camps were used to establish a penal colony where the prisoners would be forced to work hard labour. It would be 20 years before Muhammad Jafar Thanesari would be released from the Kala Pani prison. However, the penal colony would continue to be used well into the Twentieth Century.

Central to Thanesari’s case and the other ‘Wahabbi Trials’ during that period, were accusations of disloyalty to the Queen of England and sedition against the British-run Government of India. The Uprising of 1857 loomed large over all the events, but particularly the concern that the British had for Thanesari’s mobilising efforts in the Northwestern regions of India, where Muslims were rallying around two political causes: Muslim unity and the removal of the British from Indian territories.

1866 – Deoband, an anti-colonial project

As far as I know, this institution was founded after the defeat of Indians in the famous War of Independence of 1857. Therefore, sole objective of this Madrasa was to prepare freedom fighters that could compensate the loss of Ghadar of 1857.31

The above description of why the Deoband University was established came from one its founding fathers and scholars, Maulana Qasim Nanautavi. Those around him agreed that the humiliation the Indian people had suffered as a consequence of the British retaliation to the Uprising required a long-term plan. In 1866 the University was officially opened, and among its students was Mahmudul Hasan, who would go on to be the first student to graduate, and later its principal. According to accounts, within his first three years, Mahmudul Hasan had memorised the Siha Sitta (six certified hadith collections) directly from Maulana Nanautavi, who had himself fought the British in 1857.32

In 1873 Mahmudul Hasan graduated from the University, within two years becoming a senior teacher within the institution and by 1888 being unanimously declared the principal of the college.33

Around the same time as the opening of the Deoband University, Maulana Nanautavi and his trusted disciples began to lay the seeds in the Northwest Frontier region for an operation that would in the future be the base of operations for their anti-colonial struggle.34 This secret mission was kept very much secret from the daily activity of the Deoband, however, early into its history, the British were suspicious of their motives. Barbara Metcalf believes that this was due to a British fear of Muslim mobilisation that was motivated by a devotion to Islam over all else,

What cause, then, was there for official suspicion of Maulana Mahmudul Hasan, the school, or its leadership in general? From the beginning the Deobandi ‘ulema, like virtually every other institutionalized group in British India in the late nineteenth century, had expressed their loyalty to the Crown in the aftermath of the brutally repressed rebellion of 1857. It was no small achievement to gain credibility for this stance given the Muslims were disproportionately blamed for the uprising and some of the ‘ulema specifically targeted.35

These suspicions would ultimately lead to the discovery of the Silk Letter Conspiracy in 1915, orchestrated by Mahmudul Hasan and until that time, possibly the most intricate pan-ummah plan to destabilise British interests not only in India, but across the Muslim world.

1871 – The Indian Musalmans

The anti-sedition sham (‘Wahabbi’) trials that were conducted by the British in Ambala, Patna, Calcutta and London had consequences, particularly as word spread over the procedural impropriety in the law, which denied the defendants any scope to adequately gain access to the Rule of Law. On 20 September 1871, a Punjabi Muslim named Abdulla stabbed the Chief Justice of the Calcutta High Court, Justice John Paxton Norman.36

This incident served as the ideal platform for WW Hunter to release his infamous study on the Muslim population of India on 3 October 1876. The assassination of Norman led to questions being asked about the nature of Islam in India and reflections on whether or not it was even possible for Muslims living in the Empire to be faithful to the Queen. As written by Hunter,

The Musalmans of India are, and have been for many years, a source of chronic danger to the British Power in India. From some reason they hold aloof from our system, and the changes in which the more flexible Hindus have cheerfully acquiesced, are regarded by them as deep personal wrongs.37

Hunter was quick to recognise the ‘pan-Islamist’ approach taken by the Muslim leader Sayyid Ahmad Barelvi in Yaghistan and Afghanistan where the tribal belt was coalescing around a distinct Afghan jihad to repel the British from invading. Hunter was particularly concerned, however, with the role that was being played by those within the major part of India in assisting these rebel forces in the northern regions. Cases such as Muhammad Jafar Thanesari’s only served to highlight the view that while Muslims in India pretended to be loyal to the Queen, they were in fact ready to engage in acts of betrayal by working against British interests elsewhere. According to Ilyse Morgenstein Fuerst, Hunter’s work in assessing the Muslim population of India became central to the way the British respond to any threat, especially as revolution to British rule had become a “stark reality”. If Muslims could be united in India based on their concern for their faith, then they could technically become united across the whole Muslim world, thus harnessing the greatest potential to disrupt the interests of Empire.38

Morgenstein Fuerst goes on to explain,

Pan-Islamism relies on the premise that Muslims can and ought to be unified per their religious identification. For many imperialists, pan-Islamism recentered the idea of Muslims as threat: in this ideology, long-standing and historical differences among Muslims ceased to matter, leaving intact the notion that Islam was religion and law, and as such, binding to Muslims above all other authority. Pan-Islamism is related to jihad because each term recursively reinforces the other. Jihad is a legal category that British imperialists feared because it insinuated widespread and mandatory warfare of Muslims. Muslims, as we have seen above, were imagined as a unified collective, with all differences superseded by Islam’s legalism and literalism. Pan-Islamism serves to prove both the idea of a sui generis Muslim identity as well as produce it anew. Circularity does not disprove these claims, but rather reinforces their logic and truth.39

While at this stage, the formula of ‘pan-Islamism’ might not have been in vogue among Orientalists like Hunter, the understanding of it as a specific idea was located in their use of the term ‘Wahabbi’, as with the accusations levelled at Thanesari. For the British, in the view of Marcia Hermansen, ‘Wahabbi’ was the pre-cursor to what would eventually come to be known as ‘pan-Islamism’ – both of them equally pejorative in their aim of creating a category of Muslim to be feared.40

Ultimately, Hunter was concerned about maintaining British power, and so presented Muslims as a racialised category to be feared. In his survey of the jihad over varying historical contexts, Faisal Devji, wrote of Hunter in his Landscapes of the Jihad,

[I]t comes as no surprise that Hunter’s recommendations to his government should bear a striking resemblance to those bruited about the United States today. These include criticisms of past British policy in the Muslim world, calls for more stringent security and surveillance measures, as well as an emphasis on the reform of Muslim religious and political life, particularly by way of educational institutions.

In fact The Indian Muslamans simply assembles European stereotypes about the rebellious nature of Islam, Muslim fanaticism and the political threat of Pan-Islamism into an argument that is ambiguous.41

Increased suspicion and repression of Muslims, particularly through the mass expulsion to prison islands such as Kala Pani resulted in a great deal of disenfranchisement with the British. This trend only continued to increase as stronger measures of securitisation were brought into law and practice.

1872 – The assassination of Lord Mayo at Kala Pani

The degree of contempt towards the British response to the Indian uprising manifested itself at micro levels across India. British anxieties about dissatisfied and restive Muslim populations were being constantly tested. After the killing of Chief-Justice Norman, on 8 February 1872, the Governor-General of India, Lord Mayo was assassinated at Port Blair in the penal colony of Kala Pani. His assassin, Sher Ali, was a former police officer from Peshawar, who had been sent to the island prison and was serving his sentence.

Lord Mayo himself was publicly vitriolic in his response to the ‘Muslim problem’. Prior to leaving Calcutta to visit Kala Pani, he declared his intention to destroy the ‘Wahhabis’. This was already very much a reality for Indian Muslims, and as the owner of the newspaper The Pioneer, George Allen, described, “By the end of September 1857, Delhi was a ghost town, entirely cleansed of Muslims who were now increasingly viewed by the British as the real enemy.”42 When Lord Mayo arrived at Kala Pani on 8 February 1872, the previous fourteen years had seen the prison population swell from the original 200 to 7,000 – including 900 females. The population of the penal colony totalled 8,000 including 200 police.43

Among the prison population, there were those who had been tried for sedition at Ambala in April 1864. This included the likes of Muhammad Jafar Thanaseri (mentioned above), Yahya Ali and Maulvi Ahmedoola. They had initially been sentenced to death by hanging, which was later commuted to being sent to Kala Pani as the British did not want to make them into figures of martyrdom. It was later assumed that these religious figures may have had some involvement in encouraging the actions of Sher Ali, although this was never proven. One indicator to fellow inmates that Ali was planning something was the information they received that he had prepared gifts of sugar sweets for his Hindu friends and flour cakes for the Muslims, expending all the money he had remaining.44

Sher Ali hailed from the famous Afridi tribe located in the Northwest Frontier Province of Pakistan. He had served as a cavalry trooper for the British and later took on the role as a mounted orderly for Reynell Taylor, who had rewarded him with a horse, pistol and certificate. Taylor himself had been heavily involved in the suppression of those involved in the uprising and had for some time been warning of its prospect. Sher Ali was so trusted by Taylor that he was even permitted to take care of Taylor’s children.45 Sher Ali assassinated Lord Mayo by hiding in a concealed location behind a rock, and as Mayo and his security detail passed by, was able to jump out and attack him by stabbing him twice in the back. Ali presented no resistance during his arrest and the British immediately went into a state of alert. According to the historian Helen James,

The official report documenting the questioning of the assassin the following day, in identifying the motive for the deed, uses the word jihad on numerous occasions to explain Sher Ali’s reasons for his actions. The context of the report, penned amidst ongoing British fears of another uprising like that of 1857 and the recently concluded Wahhabi trails at Amballa, signals the authorities’ consciousness of the historical continuum of jihad, which was confronting them in India, the Punjab, the NWFP and other parts of their empire. (In 1885 General Gordon was murdered in Khartoum, the Sudan, by another Mahdi).

When brought before the court, Sher Ali had little to say about his actions, but there remained little doubt as to his motivations, saying that he would seek the justice of the next life for his actions.46 The actions of individuals such as the assassin of Makeson, the killer of Chief Justice Norman and those of Sher Ali only served to place under greater scrutiny the problem of the Sepoys in 1857 – that even those who fought and killed for the colonisers, had the potential to turn on their colonial masters in response to their treatment and motivated by their individual religious and ethical convictions. Although there was little in the way of a formal programme of unification of the ummah within India, there were enough indications that Muslims were already living that wider global concern.

1876 – Abdulhamid II and the Ottoman push for Muslim Unity

The intensification of colonial endeavours in South Asia, South East Asia, Central Asia the Middle East and North Africa resulted in a number of calls being made by repressed Muslim communities to the Ottoman Sultan – they desired direct military intervention in the name of jihad. This moment allowed for increased discussions among Muslim intellectuals on the role of the Ottoman state in relation to those who ostensibly sought the power of the Sultan in aiding them in their issues. According to Pankaj Mishra, it was not until 1872 though that ‘Muslim Unity’ as a specific political philosophy, was mooted by the Ottoman intellectual Namik Kemal.47

Many of the scholars writing about the early modern period insist on exceptionalising this moment from the longer history of Islam. I cite Azmi Özcan at the beginning of this paper, who points out that there were many instances of political unification prior to the late 1800s. There are factors that need to be borne in mind when the claim of a new idea within Islamic discourse is made, particularly in an ever-more globalised and industrialised world. For instance, Al-Sulami (d.1261), writing his tract on jihad and positing a seemingly new concept of it being defensive, was writing in a context where until that moment such a notion needed little consideration. Had the Crusades taken place during the period of colonisation and had al-Sulami been alive, one could well imagine that his call to defend bilad al-Sham would have been extended far beyond neighbouring principalities due to there being no notion of national boundaries within the ummah.

Colonisation, as a form of occupying power, brought with it a new form of repression, one that due to new national borders required Muslims to think of unification in ways that hitherto had been considered unnecessary. With aggression from Russia and China in the East, and from Britain, France and the Netherlands in the West, the need for a realigning of purpose became more necessary than ever for occupied Muslims on the periphery of the Ottoman Sultanate,

By the end of 1872, the first implications of this rising wave of Pan-Islamic feelings were already beginning to appear both domestically and externally. Within the Ottoman Empire it helped the growth of conservatism and Islamic patriotism. The people were becoming more enthusiastic about the religious matters and more critical about Westernization and the Europeans. The Porte had to impose certain restrictions on the activities of Christian missionaries in their attempts to convert the Muslims to Christianity. At the same time the Porte started taking an active interest in the affairs of distant Muslim lands, especially the Muslims of Central Asia.48

As Cemil Aydin notes in The Idea of the Muslim World, there is every possibility that Ottoman elites had little awareness of Muslims living in areas such as western China, but meetings in Aceh and Kashgar opened up new worlds, “due to the new journalism, which provided daily news about distant places via telegraph lines.”49 Through new methods of communication, the Muslim world, and indeed its troubles, became increasingly globalised.

On 31 August 1876, Sultan Abdulhamid II deposed his brother Murad and with the assistance of the Young Ottomans began a series of constitutional changes that attempted to bring back a notion of consultative shura through a modern parliamentary system. Abdulhamid took seriously the role of Caliph, and through this role pushed for a wider Muslim solidarity based on the ummah.50 A pious and devoted Muslim, Abdulhamid wanted to reduce the emphasis on nationalism and Ottomanism, and place the emphasis of his polity on the ummah,

We must not touch the question of nationality; all Mahommedans are brethren and any national partition wall will cause serious dissensions…In our Empire patriotism (vatanfikri) should not precede the love of religion and the Caliph.51

In the 30 year period of his reign as the last Caliph of the Muslim world, Abdulhamid’s emphasis on the ummah and the concerns of the ummah resulted in an increased feeling of a “common spiritual solidarity”between geographically distant Muslims, even if this solidarity was never actualised in any meaningful way.52

Still, this emphasis on the station of the Sultan resulted in the sharpest increase of suspicion by European powers of the rise of ‘pan-Islamism’ – a project they knew would fundamentally disrupt their intended and continued colonisation of the Muslim world.

1877 – British Plans to Restructure Governance in the Muslim World

Despite multiple British calls for formal support from the Caliphal authority, the Ottoman Sultanate actively began to work against this call as they sought to restructure the Muslim world. Consequently, British newspapers and parliamentary engineered calls for the Sharif of Makkah be recognised as the sole Caliph of the Muslim world, as in their view the authority of Islam should be held by an Arab. This Machiavellian approach was highlighted in particular by the British and French pushing the Ottomans to depose the Khedive of Egypt, Ismail Pasha in 1879, who then subsequently supported the end of Ottoman rule in Europe. While the French eventually acquiesced to Ottoman demands that Ismail Pasha’s newspaper Al-Khilafah be closed down, the seed had already been sown, especially with other Arabic magazines based in London pushing the same line.53 These debates provided the groundwork for the eventual increased interference by the British and French in the Middle East and North Africa, as they sought to use protectionist arguments to justify their presence,

As the unofficial British debate died down and the Ottomans were able to control the dissemination of the Arab exile press, the debate on the caliphate would be relaunched once again in 1880. European diplomatic correspondence in August 1880 alleged that there existed an Ottoman conspiracy to foment anticolonial revolts against the French in Algeria and the British in India and to unify all Muslims under the Ottoman caliph. By 1881, European diplomats began to use the term “pan-Islamism,” whose invention is credited to French publicist Gabriel Charmes. In the twentieth century, it would be referred to simply as “Islamism.” Pan-Islamism would become the threat European powers began to use to justify occupying Ottoman territories—the French invoked it to conquer Tunisia and the British to acquire Cyprus.54

The work of Joseph Massad informs us that in 1880 a memorandum was drafted by the former diplomat Wilfred Scawen Blunt, claiming that it was in the interests of the British to transfer the authority of the Caliphate to the Arabs, even going on to publish a book in 1882 explicitly titled The Future of Islam. What Blunt found was some support for this proposition in the “dream of some few liberal Ulema of the Azhar,” but he also felt that this would need to be brought about in subtle ways, rather than a direct intrusion by the British government.55

The express wish of Blunt would take a further 36 years before being realised in the Arab Revolt of 1916. During that period, the spectre of the ‘pan-Islamism’ threat was deployed with great efficacy in order to justify all manner of interventions, both militarily and through diplomatic efforts. The period produced its own counter-colonial projects that took a number of different forms, but were pushed to a great extent by the wandering Don Quixote-esque figure of Jamal al-Din al-Afghani.

1882 – Jamal al-Din al-Afghani and the Counter-Colonial Project

In his narrative of the mobilisation and organising against colonial interests in the 1800s, Pankaj Mishra centres Jamal al-Din al-Afghani in From the Ruins of Empire. The narrative sets out the travels and attempts of a wandering intellectual who, born in a Shi’a family, goes on to equally find patronage and exile within the Muslim world as he sought to push for Muslim unity against ever encroaching colonial regimes. Central to al-Afghani’s belief, was the humiliation he felt at the state of the Muslim world as a subject of European dominance. In the late 1870s, al-Afghani wrote to the newly initiated Caliph Abdulhamid II of his intense concern for the ummah.56

The somewhat radical or maverick approach al-Afghani took resulted in his falling out with various Muslim leaders, but in particular, the independence of this thinking led to pressure being brought on him. Despite some claims that he was the key figure pushing for Muslim unity, there were others who were equally engaged in this programme. It was in 1880 that Nusrat Ali Khan, a Muslim from India, convinced the Ottomans to allow him to publish the journal Peyk-i Islam (Courier of Islam), which allowed for him to push for the idea of Muslim political unity, which ultimately the British demanded the Ottomans close down even though they had permitted distribution in India.57

The encroachments of the French in Tunisia and the British in Egypt escalated the publications of material that sought to draw attention to the evils of colonisation but also acted as a clarion call to bring the Muslim world together in a vision of international solidarity based on collective faith. Having been exiled from Egypt after the British occupation, al-Afghani teamed up with his protégé Muhammad Abduh, and they began to publish their ideas of Muslim unity from Paris through the journal al-Urwa al-Wuthqa (The firmest bond), which was distributed across the Muslim world. As opposed to ‘pan-Islamism’, the term used by the French and British, these men advocated for al-Wahda al-Islamiyya (Islamic unity) – a notion that presented a somewhat wider and deeper sense of connection beyond mere political unity.58

This became increasingly important as the British considered how they might maintain their control in Egypt. They understood that bringing Muslim troops from India to Egypt would facilitate an active cross-fertilisation of ideas between Muslim people, potentially causing them trouble in the future,

Rippon’s apprehension was to the extent that he did not like the idea of sending Indian Muslim soldiers to participate in the campaign against Egypt. He feared that every soldier sent to Egypt would be exposed to a hostile and fanatical population and would return to India as an apostle of Pan-Islamism and focus of intrigue against the British. But the assurances of the India Office were a great relief to Rippon. “As long as the Sultan is even nominally on our side”, he wrote “I do not expect that we shall have any cause for anxiety; but if he were to declare against us, there would probably be a great alienation of Mahomedan sentiments”59

Even as they sought to occupy Egypt, the British were fully aware of the extent to which their goodwill with the Ottomans ensured their ability to ‘control’ the Muslim population of India, by reducing the level of discontent with their colonial manoeuvres. In an environment of the intellectual work of al-Afghani and others, this produced contestations they were forced to manage. In a somewhat inverted irony, considering contemporary denials of Islamophobia across the world, the European powers claimed that Muslim intellectuals developing notions of solidarity based on Islam were promoting, “xenophobic anti-Westernism that the Ottomans could use against British interests,” although this was rejected by Muslim intellectuals on the grounds that Muslim solidarity was based on a desire to end Western domination in the Islamic world.60 Ultimately, the British understood very well the precariousness of their mission considering the widespread discontent that was developing among Muslims – one that was only kept in check by the word of the Sultan.

In Egypt, Wilfred Blunt worked with Ahmed Urabi to detail a memorandum that was eventually published in The Times in 1882. Its purpose was to detail the possibility of a nationalist agenda in Egypt that would be acceptable to both the British and the Egyptian people. Even at this stage, where ‘pan-Islamism’ was considered to be a threat to colonial ambitions, the memorandum paid the term lip service in recognising the allegiance of Egypt to the Ottoman Sultan. The approach in Blunt’s previous work in trying to lay out The Future of Islam came to be softened by his interactions with Urabi and the latter’s own self-professed love for the Egyptian nationalist cause, albeit one caged within a paradigm of liberalism.61

Regardless of their actual preferred form of governance for the Muslim world, the work of intellectuals in the East within the counter-colonial world consistently centred the notion of Muslim unity. Whether that took the form of nationalisms that remained connected through the figurehead of the Sultan, or through the political expansion and direct sovereignty of the Ottoman Empire, the notion of an ummah-centred politics retained its centrality in much of the discourse – one that even figures like Wilfred Blunt (who had done so much to initiate the dismantling of Ottoman rule) came to accept.

1895 – Quilliam and the defence of the Ummah

While Muslim groups in India and Egypt were preparing a long-term strategy to remove the British from their territories, an English aristocrat and lawyer, William Quilliam, publicly declared his belief in the Muslim faith in 1887. He began a small movement in the UK that concerned itself with the affairs of Muslims around the world, as well as work locally on issues of social justice.62 As the proto-Muslim social and global activist/scholar, Quilliam spent much of his time attempting to use his position within British society to aid the causes of Muslims around the world.

Quilliam was famous for having intervened in public discourse in relation to foreign affairs. Where the British would enter into Muslim lands, he would be open in his criticism of their policies, but would support the British where no offence was made against Muslim peoples. Soon after being granted the title of ‘alim by the Sultan of Morocco, he used his position in order to issue a fatwa (legal ruling) against British intervention in Egypt and in particular Sudan that is worth reproducing in full,

In the name of Allah, the most merciful the compassionate!

Peace to all the True Believers to whom this shall come!

Know ye, O Muslims, that the British government has decided to commence military and warlike operations against the Muslims of the Soudan, who have taken up arms to defend their country and their faith. And it is in contemplation to employ Muslim soldiers to fight against these Muslims of the Soudan.

For any true believer to take up arms and fight against another Muslim who is not in revolt against the Khalif is contrary to the Shariat, and against the law of God and His Holy Prophet. I warn every true believer that if he gives the slightest assistance in this projected expedition against the Muslims of the Soudan, even to the extent of carrying a parcel, or giving a bite of bread or a drink of water to any person taking part in this expedition against these Muslims, that he thereby helps the Giaour (infidels) against the Muslim, and his name will be unworthy to be continued on the roll of the faithful.

Signed in the Mosque of Liverpool, England, the 10th Day of Shawal, 1313. WH. Abdullah Quilliam Sheikh al-Islam of the British Isles.63

Despite having come under criticism from some quarters of Muslims in India for pronouncing such a fatwa, Quilliam reiterated that as the Muslim body, their collective goal should be the establishment of the “world for Islam”.64

Quilliam’s focus on the Islamic identity as being the ultimate concern of the Muslim when considering his relationship with the Caliphate as well as his/her co-religionists resulted in him clarifying on a number of occasions the importance of such a relationship. In response to Lord Cromer in August 1906, Abdullah Quilliam wrote in The Times that Muslims around the world were angered by British presence in Egypt because of their policy to force the local population to choose between, “loyalty to an earthly ruler and loyalty to their religion.”65 For him there was no possibility that there could be any choice in the matter. Quilliam’s position however has come under scrutiny as his dual allegiances to the British and the project of Muslim unity were questioned by his contemporaries as being too open to a Muslim world united under the protection of the British.66

1906 – The Tabah and Dinshaway Incidents

The middle of 1906 brought two incidents that reverberated across the Muslim world and resulted in a great deal of consternation for the British in terms of their implications across the wider Muslim world. The first took place in Tabah, Egypt, in May 1906 where the Ottomans sought to extend their railway line. The British took exception to Ottoman presence in Tabah and although the Ottomans quickly agreed to leave, the British understood that even for their wider interests, the situation might carry implications,

The Indian Muslims were extremely perturbed at the outbreak of the dispute. Several mass meetings expressed the earnest desires of the Muslims that the dispute should be solved amicably. The Viceroy was sent numerous petitions requesting him to use his influence to persuade the British Government to avoid an Anglo-Ottoman war. The Indian Government was also worried, for it predicted, in case of a war, a declaration of jehad by the Sultan Caliph. Thus the end of the conflict was a great relief to the Indian Muslims, but only for the time being, because the signs of a more serious rupture between Britain and the Ottomans were already becoming clear.67

The second incident took place only a month later in the Egyptian village of Dinshaway. On 13 June 1906, British officers went pigeon shooting in the village despite numerous protests from the villagers in the past over what the British officers had been doing. The villagers’ pleas remained unheeded resulting in a fight that broke out between the officers and some of the men. It was during the fight, that the gun of one of the officers was discharged, wounding four of the villagers and killing one. This escalated the situation and the officers were beaten by more of the villagers until one officer attempted to go back to their barracks to seek help – he died from exhaustion on the way. A farmer caught resuscitating the collapsed officer was thought to have killed him, and he was summarily executed.

The result of this incident was quick and brutal. A special tribunal was convened in order to try the villagers within two weeks, sentencing 21 of the villagers to punishments ranging from imprisonment to lashes of the whip to death by hanging. To further the spectacle of British retribution, the entire Dinshaway village was forced to watch the punishments being carried out. The Egyptian writer Qasim Amin described the feelings of the wider population following this incident,

Everyone I met had a broken heart and a lump in his throat. There was nervousness in every gesture—in their hands and their voices. Sadness was on every face, but it was a peculiar sort of sadness. It was confused, distracted and visibly subdued in the face of superior force.68

The activities of the British and in particular Lord Cromer had already been identified as the seat of insults against the Egyptian people, but also Islam more generally. A year after the Dinshaway executions, the poet Ahmad Shawqi received widespread acclaim for his stinging qasidah (poem) A Farewell to Lord Cromer which was memorised across the Arab world. Shawqi was not a nationalist, but very much viewed Cromer’s tenure as de facto ruler of Egypt as one that was an attack on Islam itself.69

On the anniversary of Dinshaway, Shawqi would double down on Cromer by referncing him as a despot of the past, “O Nero, had you lived till the reign of Cromer/ You would have known how sentences are carried out.”70

Ahmad Shawqi’s verse reflected the mood that had spread across much of Egyptian society, in fact much of the Arab world. As will be evidenced in the following section, the news of what had taken place had travelled far and wide. The British were aware of this and rather than reflecting on their own oppressive actions against the Dinshaway villagers, instead obsessed on the potential threat that emerge from ‘pan-Islamists’ over the perception of their actions in the Middle East. In his analysis of anti-colonial poetry, Hussein Kadhim cites The Times correspondent based in Alexandria reporting after the executions,

The condemnation of the Dinshaway criminals has produced a whole-some nervousness among many of the supporters of the Pan-Islamic movement, who realize that any anti-European movement will be met by drastic measures on the part of the government…That fanatical feeling is widely spread among the rabble of Alexandria and Tanta is well known. But the Tanta mob has been profoundly impressed by the consequences of the Dinshaway incident, and in Alexandria there are signs that the anti-foreign excitement is subsiding.71

The initial assessment suggested that the harshness of the sentences produced the effect that they had hoped, which was to neutralise mobilisation against the British through a strong, disproportionate show of strength. This was somewhat short lived as by 1907 Mustafa Kamil founded the Hizb al-Watani (Nationalist Party) in response to the Dinshaway incident. Kamil’s position was quite simply that the British should leave Egypt entirely. The rise of this nationalist sentiment built on teachings of al-Afghani and Abduh, as emerging nationalist figures such as Sa’ad Zaghloul had been students of these intellectuals, and thus still felt connected to the Ottoman Sultanate. The disenfranchisement they felt at the presence of the British resulted in a number of nationalist secret societies, such as the Mutual Brotherhood Society, who went on to assassinate the Egyptian Prime Minister Butrus Ghali in 1910 for taking pro-British stances.72

1906 – The British Criminal Intelligence Division Investigation into Pan-Islamism

The clearest example of the way the British saw the threat posed by ‘pan-Islamism’ as a matter of criminality and sedition came in the form of a Circular Memorandum distributed from Simla on 9 August 1906 by the Director of Criminal Intelligence. The Circular expressed concern over agents on diplomatic missions to draw the Muslim world closer.73

This series of communications, issued two months after the Dinshaway executions, indicates that the British viewed their Muslim subjects through the lens of securitisation that was linked to their belief, but in particular over how they placed any concern for the wider Muslim ummah within the nexus of their religious commitments. While much of the Circular focuses on the various intrigues between the Ottomans and their German allies during this period, there is a report by a political agent in Bahrain, whose response to the question of ‘pan-Islamism’ is instructive of the ways in which the British expressed their anxieties. Sent in December 1906, the Bahrain agent expresses that he does not believe there to be a significant ‘pan-Islamism’ sentiment in the region, largely because the majority of the population is Shi’a, and so less inclined towards an Ottoman Sultan. There is an extended discussion of the mentioning of the Caliph’s name in the jummahkhutbah – but this is put down to convention rather than having any political significance. The view of the agent largely rests on the relationship that the British officials have with the tribal elites of Bahraini society.74

Writing of the general sentiment among the non-tribal Arab population of Bahrain, the agent provides a somewhat contrasting image,

It is an awakening at present no more than a feeble beating of ripples in a standing pool. It is an awakening to the lost position of the followers of Islam and a desire to advance, not as a common kin of Bahrain or as a separate entity, but as a member of the conglomeration of races under Islam. The impossibility of such a feat is not recognised, and its feasibility is the hope of many a merchant Arab, who have seen something of the world and who regularly read and discuss this subject, enthusiastically pursued by the Egyptian press. It was this class of the Arab which was exercised at the Tabah affair. They took up the Turks’ position there as their own. These Arabs, small in number they are, were, however not exercised so much as the Holi class. The latter, a hybrid community as they are without a national concern in which they could centre their affections and aspirations, have taken to adore the Sultan, they also feel the nationalist movement in Egypt as their own, and their feelings during the Tabah and Dinshwai incidents had reached a pitch. ‘Al Liwa’ was then being read with great enthusiasm and loudly in shops amass and majlises, and many an ignorant people gathered to hear tales of injustices and did not leave without being affected. Even it is said that tears were shed, moved by intense sympathy for the Egyptians.75

One of the insights that can be gleaned through these communications relates to the way in which the Muslim world communicated the outrages carried out by the colonial administrations, and the way in which the authorities chose to understand that concern. Rather than making reparations for the violent actions, the British instead chose to pathologise the concerns of everyday Muslims as an example of a threat that was posed to their interests. The events of Tabah and Dinshaway provided a perfect example of the way that would take place.

1915 – The Silk Letter Conspiracy

Events in India were leading to tensions between the British and various populations in the region, particularly those areas with high concentrations of Muslims. In 1903, the Viceroy of India, Lord Curzon, announced that he intended to remove the areas of Chittagong, Dhaka and Memonsingh from Bengal, and instead confer these areas to the country of Assam. Despite their desire to remain as part of India, the protests by the Bengali population fell on deaf ears and on 5 July 1905, Bengal was partitioned.

In response, the people of Bengal began to rebel and adopted a three-part strategy: to boycott British goods, to only rely on local sourced produce and finally to terrorise the colonial regime. Even states outside of Bengal were horrified by the partition, and protests took place in states such as Bihar and Orissa. This campaign of resistance peaked on 11 April 1908, when as Justice Kings Ford was travelling on a train through Muzaffarpur, a hand grenade was thrown into his carriage in an attempt to take his life. It was only after five years of constant protests, that the people of Bengal finally succeeded in forcing the British to abrogate the partition in 1911.

Incidents such as this only convinced Mahmudul Hasan of the need for a unified response focused on putting an end to colonial rule. It was not until 14 November 1914, that such an opportunity presented itself. On this date, the Ottoman Sultan, officially declared jihad on the British, thus bringing about a tension for Muslims in the First World War. For the colonisers, the moment presented itself as an opportunity to cooperate with one another too. The Ottoman Empire having explicitly issued a call for jihad, meant that all the anxiety the colonial states had around their Muslim subjects, had now intensified. According to William Polk in Crusade & Jihad,

When the Ottoman Empire called for a holy war, each of the imperial powers expected revolts: Britain in India and Egypt, France in North Africa, and Russia in the Caucasus and Central Asia. Each ruled over millions of Muslims, and each was warned by its security services that the Muslims were “seething.” Each expected an upsurge of nationalism—whether ethnic as in “Pan-Turkism” or religious as in “Pan-Islamism”—and regarded it, at least before the terrible battles of the war, as even more dangerous than its European adversaries. Fear of jihad was augmented by imperial ambition. In varying degrees, all three powers were affected by both fear and greed, but it was Britain that played the lead role.76

Colonial coercion of Muslim subjects depended largely on the obsequiousness of Muslim elites, whose cooperation permitted the ongoing control of larger populations. Rulers in Zanzibar, Nigeria, Egypt, Sudan, Persian Gulf, India and Malaya all contributed to the suppression of anger that larger Muslim populations had at the ongoing colonial rule.77

Working with Ubaidallah Sindhi, Shaykh-ul-Hind Mahmudul Hasan, fully aware of the discontentment across the Muslim world, began the process of engaging with Deobandi students in the Northwest, all in the hope of building the platform for a movement.78 Sindhi described how after a fifty-year period of planning, he was finally allowed to learn of the true intentions of his teacher in 1915 – to politically unite the ummah.79

The plan was to build a standing army in Yaghestan (the frontier region of Pakistan) by sending young mujahideen from India to join them. They would be supported both militarily and financially from Muslim leaders around the world, resulting in a coalition which would be strong enough to topple the British. In an address, Maulana Ahmad Hasan Amrohawi clarified the plan in further detail.80

At the same time that all these major world events were taking place, domestically the Indian government became concerned with Mahmudul Hasan and the large following he was attracting, particularly from the northwest. Before long, associates of Hasan informed him that his arrest was imminent and that he should make plans to leave for Hijaz which he promptly did. Metcalf points out that the UK government report into subversive behaviour in the subcontinent, took the view that it was the Muslims in particular who were a problem,

The government reported alluded to above, the Sedition (Rowlatt) Committee Report, no doubt exaggerated the importance of the activities on the frontier. Moreover, it implied a “Mohamedan” dimension to the events there which is belied by the international and secular non-Muslim participation that the report itself documented. The chimera of Muslim “fanatics” on the frontier was a continuing thread in colonial ideology from the late nineteenth century on, even if belied by lack of evidence.81

It is the same Sedition Committee Report that brought the details of the ‘Silk Letter Conspiracy’ to light, which gave indications of the role the Deoband were alleged to have played in working against the British. Ubaidullah Sindhi had outlined a plan for an ‘Army of God’ that had been sewn into silk letter scarves, and transported around the Muslim world in secret. It was the discovery of these scarves in August 1916, that prompted the British to order the arrest of Hasan.82

1916 – The Internment of Political Prisoners at Malta

Although in itself a major problem for Deoband, the presence and control of colonial powers in Hijaz was a source of particular distress. After Mahmudul Hasan left India following the ‘Silk Letter Conspiracy’ and joined one of his disciples Husain Ahmad Madani in Hijaz, they found themselves at odds with the British again, as they confronted the legitimacy of the Sharif of Makkah who had been installed by the British.83

The suggestion mooted by Wilfred Blunt in the late 1800s was now being brought into fruition by the British. They desired for the Sharif of Makkah to convince Mahmudul Hasan to sign a document that would recognise his claim to the Caliphate, and the illegitimacy of the Ottoman Sultan84– failure to do so resulted in Hasan and his companions being arbitrarily detained and sent to the prison island of Malta. The British attempted to co-opt the message of Islam and its jurisprudence to serve its own interests, an activity which much of the Muslim world saw through. By using Islamic interpretations to serve their own purposes, they attempted to lend legitimacy to their own actions,

The problem had to do with a declaration that reproduced an argument about Islamic authority initiated by the Arab Bureau in Cairo and other British officials claiming expertise in Islam. This argument was predicated on the assumption that there was a happy coincidence between British geo-political ambitions and “correct” Islamic interpretations. It denounced the Turks as infidels, kafirs. It also asserted that the “caliph,” the holder of that ancient position linked to the earliest years of Islamic rule, and later adopted by the Ottoman sultan, could only be of Arab descent. It thus presumed to give complete legitimacy to the Sharif’s revolt against the Ottoman overlord. It also assumed that “Islamic doctrine” not, for example, good governance, was all that any Muslim cared about. In fact, no Arab units of the Ottoman army every came over to the Sharif; a few thousand tribesmen, paid off by British money and famous thanks to Colonel T.E. Lawrence, “Lawrence of Arabia,” formed his troops.85

Mahmudul Hasan and Madani were not willing to compromise on their theological convictions for sake of granting legitimacy to the Sharif, however Mahmud was careful to mention that he was not involved in any plots. He explained at his arrest that he did in fact prefer Turkish rule to that of the Sharif on the ground that the Turks were more just and more generous, whereas the Sharif “beats and imprisons without inquiry,” even, he said, killing children and outraging women. Ultimately, refusing to acquiesce to British demands that the Indian scholars engage in khurooj [splitting] from the authority of the Ottoman Sultan, resulted in their detention from 1915 to 1920.

The prison island of Malta became a seminal site for British repression of Muslim political ambitions. Sa’ad Zaghloul, the Egyptian leader of the nationalist Wafd party, was detained there for demanding national recognition. On the day of his detention, a 13-year-old schoolboy was inspired by Zaghloul’s detention to deliver his own patriotic speeches, “at meeting halls and mosques, where the spirit of the sacred revolution was breathed into all”— that teenager was Sayyid Qutb.86

As Qutb’s biographer John Calvert writes,

the young Qutb appears to have followed the nationalist mainstream in interpreting the Wafd’s call for independence in terms of Egypt’s loyalty to the civilisation of Islam and the institution of the caliphate.87

There is a tendency of many to present Sayyid Qutb’s trajectory towards being involved in an Islamic movement as being much later in life, and yet such a narrative belies the complex role that his direct experience with colonisation played. While the British were always concerned about the threat of ‘pan-Islamism’, it is worth noting how a young Qutb never lost the anxiety of having British firearms levelled at him while he was still a child growing up in his village – the violence of that moment never left him.88

The corollary of repressive acts in India and Egypt during World War I is a reminder that Muslim suspicion of the British was not simply based on their ‘pan-Islamism’, but rather was very much tied to their direct experience with colonisation. It was the British who securitised and pathologised their responses, so that the emphasis was always on a racialised idea of the Muslim threat. In 1915 the British enacted the Defence of India Act – a piece of legislation that brought in wide ranging draconian restrictions on civil liberties during the war years – the emphasis was entirely on repressing any political agitation. This act resulted in many interments, other than those that took place in Malta. The internal dynamics in India during the First World War became bitterly intense as British war propaganda increased, attacking the Ottoman Sultan, all the while almost six million subjects of the British Empire died due to both famine and an influenza epidemic. Instead of trying to ameliorate the resentment felt by the Indian population, the British enacted the Rowlatt Acts in 1919, used as a method of suppressing public protests and any form of dissension or sedition. A public meeting at the Jallianwala Bagh in 1919 to discuss the Rowlatt Acts resulted in General Dyer opening fire on a large crowd of protestors, only cementing the brutality of the regime.89

Ultimately, there was a complex series of violent repressive colonial acts, that instead of being held to account, were seen as clarion calls for the destabilisation of empire through ‘pan-Islamism’. The fears that British intelligence internalised, resulted in increased repression and curtailment of civil liberties and the rule of law. This is striking in a contemporary context as moments of serious outrage among Muslim communities, such as the images that were exposed from the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, or the publishing of cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad (saws), were seen by culpable/complicit states through the lens of the hostile reaction they might evoke. They were seen as moments to be managed, rather than seen as moments that required accountability. In 2009, US President Barack Obama refused to publish the images from Abu Ghraib in case they might, “further inflame anti-American opinion,” rather than focusing on holding perpetrators of those horrors to account.90 This anxiety over reactions rather than justice has remained at the centre of western anxieties of the ways in which Muslims respond to outrages against the ummah.

The case against ‘Islamism’

The narrative set out in this document focuses heavily on colonial anxieties that existed around ‘Islamism’ and ‘pan-Islamism’ as a threat to the colonial order. Some will argue that ‘pan-Islamism’ is a specific historical moment, but as I hope I have evidenced throughout this document, ‘pan-Islamism’ in the way that it was used by the British, French, Dutch and Russians, did not equate to ideas around Muslim unity that were being promoted by Muslim intellectuals and the Ottoman Sultanate. If, for no other reason, we should scrap the use of the word ‘Islamism’ because of its colonial history. The ubiquity of a term in European political or scholarly vernacular should not signify its accuracy or correctness. As I mentioned in my introduction, what is of most importance regardless of acceptance of this call is the extent to which Muslims globally can decentre from the West’s framing of ‘Islamism’ as they consider the needs of the global Muslim ummah.

To set out my case further, I rest my argument on four main contentions:

- The colonial history of the words ‘pan-Islamism’ and ‘Islamism’ is inextricably tied to the notion of a threat that requires a security response.

- The contemporary popular use of the word ‘Islamism’ is nearly always tied to militancy, extremism and violence, and so cannot be rescued from within academia. The evocation of the word presents images of violence. Unlike words such as ‘Muslim’, which may now be regarded in the West as evoking similar fears, ‘Islamism’ operates as a hydra, where it is simultaneously violent and meaningless in its operation. Violent, in the impact it can have, meaningless in the amorphous nature of its use.

- That within the framing of the global War on Terror, the accusation of ‘Islamism’ in itself draws heightened suspicion and surveillance, leading to many forms of violence enacted by the state. Similar to the framing of the ‘good’ and ‘bad’ Muslim, ‘Islamism’ carries a significant degree of academic cover that operates outside of its ubiquitous significance – academic use cannot rescue the way the word has been politically instrumentalised.

- It presupposes that only certain forms of faith-based political expression are ‘Islamist’. I make this point to suggest that quietist expressions of faith within the political realm, are no less political in their maintenance of political authority – indeed these positions are often used to uphold that authority.

1. The colonial root of ‘Islamism’

The primary aim of this paper was to connect the current discourse around ‘Islamism’ to a longer colonial history of European fears of ‘pan-Islamism’. The key to this history is not so much what ‘pan-Islamism’ meant, but the ways in which European powers considered it a threat that required a specific and oftentimes brutal response. Many of these fears were based on notions of a Muslim world that was connected through the concept of the ummah, one that the British at times used strategically to their advantage, while at other times, sought to undermine it. After the 1857 Indian Uprising, the British had little problem in invoking the authority of the Ottoman Sultan over his Indian Muslim subjects to quell disquiet among them. Yet, by the start of the twentieth century, criminal investigations were being launched into dissident Muslims in India and Egypt who were organising to unify the Muslim world. The British position was therefore based on strategic self-interest, and was purely in aid of ensuring the longevity of their imperial dominance.

As mentioned in the introduction to this paper, the accusation of ‘Islamism’ or ‘pan-Islamism’ ultimately amounts to a loyalty test. This was most apparent in WW Hunter’s 1873 report on Muslims in India, where the framing of his question indicated his predisposition towards arriving at certain conclusions: The Indian Musalmans: are they bound to rebel against the Queen? This same question has continued to be levelled at Muslims in different ways by politicians in the West. For instance, the former UK Prime Minister Theresa May’s visit to an Ahmadiyya Association in 201391 took no umbrage with their spiritual leader Mirza Masroor Ahmad describing himself as the Caliph of Islam – for the issue is not with the title, but rather where the loyalties of any community lie. The Ahmadiyya community’s overt statements and displays of loyalty to their ruling government since the time of the British Raj are well documented, and thus their framing of a Caliphal discourse to their own members is never considered to be subversive or problematic.92 This is particularly noticeable due to the narrative that has come from security circles around belief in a Caliph being a sign of extremism.93

As this paper evidences the arguments for why the colonial presentation of ‘Islamism’ is so problematic, I will not reproduce the remainder of the arguments in this case. The work done above should be enough to convince the reader that its initial use is troubling and has carried implications for the world we inhabit today. Thus, one cannot rescue the use of ‘pan-Islamism’ without accepting the violence and securitisation that accompanied its use.

2. The contemporary popular understanding of ‘Islamism’

Sometimes, the nuances associated with certain terminologies in expert or academic spaces are not transmitted so easily when the same terms are used in non-specialised discussions. Trends in media portrayal and discourses can often influence or skew public understandings of certain words, causing them to take on cultural meanings which colour our everyday understandings and usage in ways that depart from any technical definition. For example, often, when Muslims speak of ghuluu or ‘extremism’, they mean something very different to the images that are conjured up in the minds of other communities. Similarly with words such as ‘terrorism’ and indeed ‘Islamism’ – these carry popular meanings beyond how they are legally or academically understood. As Jonathan Brown rightly points out,